In Part 1, I looked at Mistakes 1 through 3, learned at my first startup in 1999. In this part, I detail some of the mistakes I learned from while trying to start my own company.

On My Own

I ended up striking out on my own in late 2000 as an IT strategy consultant with a couple of initial clients that kept me very busy. Many people said to me, “Gee, this is a strange time to be going out on your own. There’s a downturn coming.” If figured my two good clients would be enough for me to ride out the downturn.

Mistake #4: You’re not enough

Despite the dotcom bust, things were great through mid-summer 2001, even after one of my clients had to let me go due to a “no more consultants” belt-tightening move. When the second client started having revenue problems (primarily because a large part of their business was building software products for dotcom startups), I realized what I already knew: I’m no salesman. I had a hard time scaring up new business and then 9/11 hit and IT consulting dried up completely. Oops.

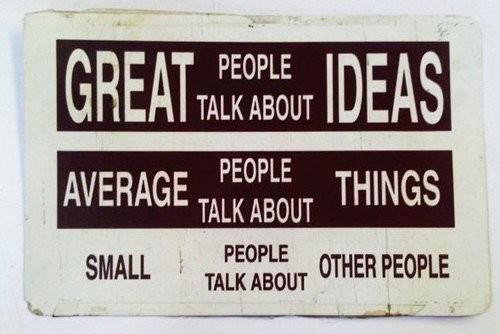

Mistake #5: Great ideas aren’t enough

I tried to start a syndicated IT advisory service, and tried to partner with other consultants, but nothing worked out. My prospects all agreed that the business problem I was trying to solve—the fire hose of information the average IT executive had to deal with—was real and needed solving. But they were all just trying to hang on during the IT Depression that lasted into 2003.

Mistake #6: Partners aren’t always an asset

I figured I needed to partner up, and so sought out other startups that I thought would be complementary. Several times through 2002 and 2003 I thought I’d found what I needed, and spent lots of time building products that never really caught on, often because my partner clung to his vision and wouldn’t, er, pivot.

The other problem with partners is they rarely will work as hard for your vision as you will. More on that later.

Mistake #7: We have no competition

Wow, do I hear this one a lot. Probably half the startups I’ve been involved with believed this. Our product is unique and there’s nothing out there like it, so we have no competition. The implication is that our unique product is going to be easy to sell because people will see it, realize there’s nothing like it, and immediately buy it.

In fact, the opposite is true. If your product is unique, chances are very good it’s going to be harder to sell, not easier. Why? Because people probably don’t know they need your unique product and, if they do, you’re going to still have to market it to them, and perhaps even educate them.

And if your product involves any kind—and I mean any kind—of behavior change, it’s going to be twice as hard to sell.

In 2003, I advised a startup that had a unique solution to a very real problem. It was many times more effective than existing solutions—by an order of magnitude.

But it was created by a teeny startup whose founder had two jobs and no money. He had a patent pending, but he didn’t even have the money to build a full-scale prototype and he refused to take any investment.

I still own a third of the stock in his company . . .

Up next: Trust, attention, and being right