Edina Note: this is an update of a 2010 update of an original post from 2001 called Breaking the Diamond: The Death of Brand.

When I first wrote this article back in 2001, it was titled, Breaking the Diamond: The Death of Brand, and eCommerce was a relatively new thing. Google was a couple of years old; Amazon was five, but not nearly the dominant giant it is today. Other current trends and concepts such as Web 2.0, social networking, blogging, wikis, and instant messaging were just ideas, if that.

Some rights reserved by Paul Townsend

Back in 2001, I said: “Imagine a day, however, when it is possible to evaluate all these product qualities instantly, objectively, and in real time. Would that not reduce our dependence on brand? And at the same time, would that not reduce the effectiveness of advertising?”

That day arrived a while ago, and brand marketers are still dealing with its aftermath. Their world is rapidly changing around them, and many still cling to a concept that is becoming less and less relevant: brand positioning.

OK, the original title of this post was a bit of hyperbole, but it’s not an unthinkable concept. Of course, there will always be brands, but the days of brand owners thinking they can control what we think about a brand may be ending.

Simon Knox said, way back in 1996[i], “In the future, it is not going to be enough simply to consider how responsive each customer group is to your brand, you will need to know how responsive your company can or should be in meeting the total needs of customers who buy from across the categories in which you compete.” Sounds a bit like a prescription for marketing via social media, doesn’t it?

Knox continues: “In traditional consumer marketing, the advantages enjoyed by a brand with strong customer loyalty include ability to maintain premium pricing, greater bargaining power with channels of distribution, reduced selling costs, a strong barrier to potential new entries into the product/service category, and synergistic advantages of brand extensions to related product/service categories (Reichfeld, 1996).”

Five years after Knox, authors Gommans, Krishnan, and Scheffold[ii] recognized that brand loyalty was undergoing a bit of a sea change, and discussed a replacement concept: e-loyalty, which leads to behavioral loyalty, the tendency to keep buying a brand:

As extensively discussed in Schefter and Reichheld (2000), e-loyalty is all about quality customer support, on-time delivery, compelling product presentations, convenient and reasonably priced shipping and handling, and clear and trustworthy privacy policies. [. . .] A satisfied customer tends to be more loyal to a brand/store over time than a customer whose purchase is caused by other reasons such as time restrictions and information deficits. The Internet brings this phenomenon further to the surface since a customer is able to collect a large amount of relevant information about a product/store in an adequate amount of time, which surely influences the buying decision to a great extent. In other words, behavioral loyalty is much more complex and harder to achieve in the espace than in the real world, where the customer often has to decide with limited information.

Traditional brands with high brand loyalty have enjoyed a certain degree of immunity from price-based competition and brand switching (Dowling & Uncles, 1997). In e-markets, however, this immunity is substantially diminished due to how easy price comparing among shopping agents is (Turban et al., 2000) and due to the fact that competition is just one click away.

I updated this post in 2010 and said, “Nine years later it is becoming clearer that behavioral brand loyalty is not only difficult to maintain online, but it’s getting more difficult to maintain offline as well. The plethora of online information Gommans, et al. referred to now includes a tremendous wealth of customer reviews, opinions, diatribes, blogs, and wikis such that the potential customer of virtually any product or service can spend days absorbing it all.”

Seven years after that, we’re drowning in content. Social selling is a thing. Brands more and more are looking for a way to hold on to and grow their franchises in a world with significantly more choices than the world of 2001 and even 2010

Marketers are no longer oblivious to this revolution in branding, and brand position. The change has been obvious since 2005, when Nick Wreden, managing director of FusionBrand, said in an article[iii] , “The number of branding failures, many based on ‘positioning,’ exceeds 90%, according to the consultancies Ernst & Young and McKinsey & Co.” The old stuff may be losing effectiveness.

The occasion was McDonald’s announcement in 2005 that it was abandoning brand positioning, which basically is a way that a company seeks to control how their brand is perceived by consumers by pushing messages at them through traditional media. At the time, Larry Light, McDonald’s chief global marketing officer, said, “Identifying one brand position, communicating it in a repetitive manner is old-fashioned, out of date, out of touch.” Light stated his position even more strongly, heralding “the end of brand positioning as we know it,” calling it “marketing suicide.”

Light was right back then, and even more right 12 years later, when brand perception is ever-more deeply affected by social media. When the millions have found their voices – online – it’s hard to compete with push branding messages delivered via conventional media, or frankly, even via social or other online media. Add in the detrimental effect of commercial-skipping digital video recorders, the move to mobile as the primary content delivery device, and YouTube as the Millennials’ jukebox , and McDonald’s move back then seems even more prescient.

Even five years ago, the strength of social to affect consumer and business purchase was apparent. A 2012 survey by BzzAgent examined the potential long term effects social media marketing can have on purchase intent. The company examined consumer purchase intent before and even a full year after the social media campaigns ended. They found that 61 percent of survey respondents were more likely to make a purchase a year after a social media campaign.

Is that a brand effect or a social media effect?

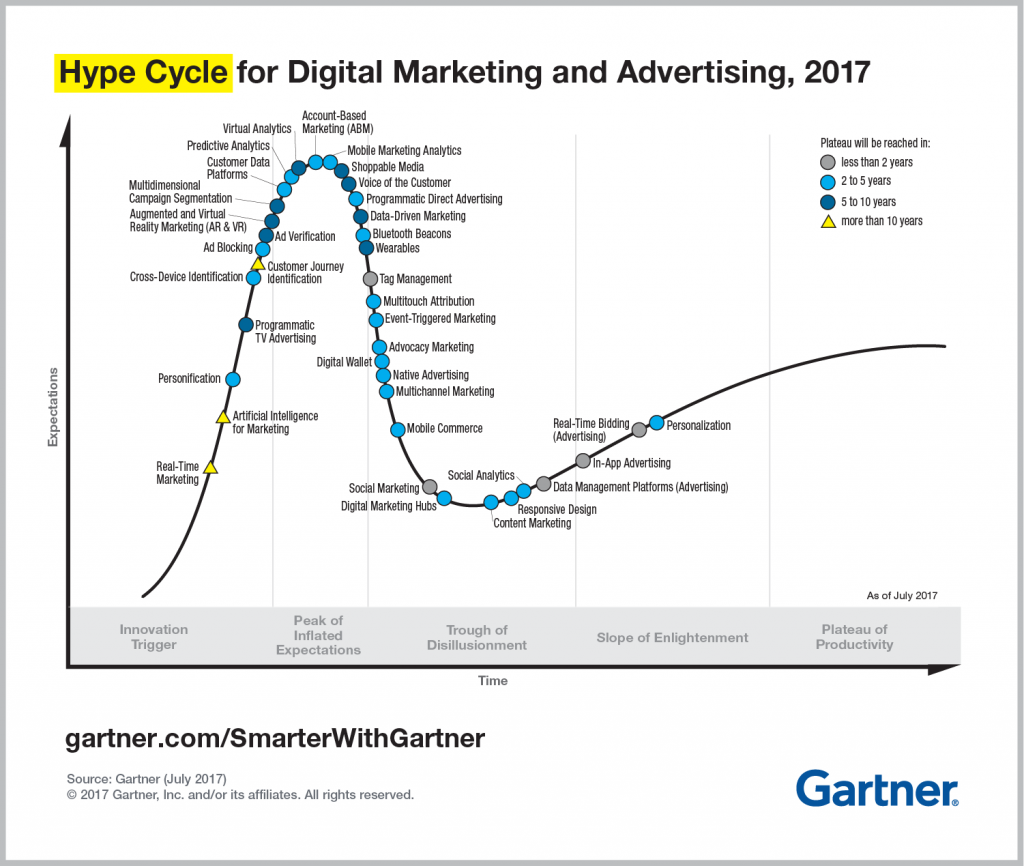

In 2017, more and more brands have learned the premise of my first book series, Be A Person, and are turning to influencers as a way to increase the power of their marketing. On the business-to-business side, social selling is cresting the Peak of Inflated Expectation and heading for the Trough of Disillusionment.

What is Killing the Brand

So what is killing the brand as we knew it? A combination of two disruptive technologies: electronic commerce and social media. Wreden says, “[. . .] consumers now buy based on research and personal value, not on [how] companies seek to ‘position’ their products.” And you know it’s true.

A great example of this one-two punch to branding’s breadbasket is my recent experience buying a desktop PC. Yes, I know. How 2010. But I basically needed a server to automatically back up all my stuff and support two 23 -inch monitors and my appetite for having dozens of Chrome tabs open at a time.

So I was in the market for a powerful desktop. I knew what I wanted, based on online research and a few visits to local computer stores. Many “brand” companies build machines in this class, and while researching HP, Dell, Toshiba, and Lenovo, I read every review I could. I found a refurbished HP that got great reviews for a price I liked and I bought it. This experience was different from my purchase of the machine that preceded it, in 2010, a laptop.

I had done the same amount of research as for the desktop, and was researching an HP laptop, which was my current frontrunner. I was almost all set to buy. But I saw one reviewer who said, “If you really want performance, get an ASUS laptop.” Seven years ago, ASUS wasn’t really in the conversation for most people. I had primarily heard of them because they make motherboards. But back then, they were not a “brand” company; they spent very little to nothing on marketing or brand positioning.

While researching the recommended laptop, I found a gamer’s laptop forum. Early on in one ASUS thread, forum participants were eagerly anticipating the release of ASUS’ N61J, which had actually occurred a few days prior to my search. As I read through the thread, I heard lots of stories about, and respect for ASUS by gamers, who arguably the most discerning of laptop owners. They were sure it was going to be a hot laptop, and, further down in the thread, when one of them actually bought one, the clamor for a review and pictures was amazing.

So I found a gamer-oriented online store in Nebraska, ordered mine, and it was everything the gamers said it would be, until it gave up the ghost last year.

Similar scenarios are playing out all over the Web right now. Big and small brands are being evaluated by actual consumers, and more and more, the little guys are winning.

The revolution against brand is nowhere near over, but, according to Wreden, “Even a top executive at advertising giant Leo Burnett is willing to stand before his CEO peers and admit, ‘the old ways of marketing are not working anymore.'”

Lack of Metrics One of the Culprits

In a very ironic trick, brand positioning has partly been done in by a lack of measurement. I say ironic, because one of the very first objections we get when pitching enterprise social media strategy engagements is, “How can we measure it?”

Social media is exponentially easier to measure than your typical brand marketing effort. Even in Postioning, one of the books that started it all 27 years ago, authors Jack Trout and Al Ries stated “mind share is more important than market share.” The authors further equated brand positioning with mind share in this passage: “Positioning is not what you do to a product. Positioning is what you do to the mind of the prospect.” But how do you measure mind share?

Today, you increasingly can. Among the concepts we teach in our social media training are Net Promoter Score and Share of Conversation. Either is more important and can be more accurate than many other standard marketing metrics, and a decent metric to use in measuring the success of your social media efforts.

Share of Conversation is the degree to which an organization is associated with the problem it seeks to solve. It is measured by the percent of all people talking about a problem online that are talking about you. This is a real measurement, and a fairly good proxy for measuring mind share.

So, yes, it’s ironic that a metric that could measure the effect of brand positioning arrives on the scene and hastens the demise of this marketing staple.

The Death of Marketing Departments?

Not to dwell too much on Wreden’s excellent article, I was especially struck by this item – remember this was written 12 years ago: “[. . .] Forrester recently reported that companies are looking at disbanding marketing departments and distributing its function among sales, customer service, etc. While that is definitely eyebrow-raising, it’s a logical outcome for a function that represents the second biggest outlay for most companies, yet cannot generate the metrics to justify those expenditures. ‘Awareness’ and ‘position’ just don’t cut it anymore in executive suites.”

Wow. Can’t say I’ve noticed this trend in the intervening 12 years, but it could happen.

But I’ll leave you with a bit more from Wreden just to show that some brands get it:

McDonald’s advocates “brand journalism,” or tailoring products and messages to both targets and media.

By recognizing that it is better served by adapting itself to customer requirements instead of preaching a “position,” McDonald’s is definitely on the right track with “brand journalism.” but the term is awkward for several reasons. A better term for this customer-driven strategy that reflects today’s branding realities is “brand wikization.”

Born from the Internet’s ability to link an archipelago of people and information, wikis are the mirror-image of blogs. While blogs reflect one person’s worldview, wikis, written collaboratively by contributors from all over the world, reflect a common judgment on an issue. Definitions depend not on what Funk or Wagnall or Webster say they should be, but on what thousands or even millions of people agree on what they are.

In much the same way, brands today are collectively defined by their customers.

I really couldn’t have said it better myself. Wikis for brands haven’t really taken off, but brand communities are accelerating. And the recent intense concentration on content curation might actually be standing in for the brand wiki concept.

So what do you think? Sound off below.

[i] Knox, Simon. ” The death of brand deference: can brand management stop the rot?.” Marketing Intelligence & Planning. Emerald Group Publishing, Ltd. 1996.AccessMyLibrary. 25 Apr. 2010 < http://www.accessmylibrary.com>.

[ii] From Brand Loyalty to E-Loyalty: A Conceptual Framework, Marcel Gommans, Krish S. Krishnan, & Katrin B. Scheffold, Journal of Economic and Social Research 3(1) 2001, 43-58

[iii] The Demise of Positioning, http://www.brandingasia.com/columns/011.htm

[iv] Advertising Effectiveness: Understanding the Value of Social Media Advertising,http://en-us.nielsen.com/forms/report_forms/Understanding-the-Value-of-a-Social-Media-Impression-A-Nielsen-and-Facebook-Joint-Study